Women’s involvement in sport has been growing in importance over the past half century, now is the time to realise real world change rather than continuing to reinforce the case for "why".

Seizing an Opportunity

Women’s involvement in sport has been growing in importance over the past half century – enshrined today in the mandate of the International Olympic Committee, FIFA and most of International Sports Federations. From the success of the internationally acclaimed “This Girl Can” campaign in the UK, to the opening of Stadiums and licensing of gyms for females in Saudi Arabia there has been undeniable progress.

There is still a very long way to go in terms of real world outcomes, but the case, and the opportunity for accelerating the increase of female involvement in sport - be it participation, fan engagement, consumerism, research and academia, PE, sport business and so on - is now compelling:

- Economic – higher levels of involvement will translate to higher economic and commercial value, whether through participation, consumption or elite performance. Women’s sport already contributes over £7bn to the UK economy.

- Health – more women involved in sport should translate to more women participating in sport, which in turn will lead to better health. Recent evidence shows incidence of diabetes is reduced by 78% amongst women classed as highly active.

- Social – involvement in sport will generate positive social outcomes relating to social capital, social cohesion, integration and community. At an individual level, women who take part in sport have higher levels of confidence, self-esteem, and a lower incidence of depression.

- Performance – as more women become involved in sport the pool of potential talent will get bigger, leading to greater elite success.

The typical debate around women focuses on how things should or ought to be, how to value them, which things are good or bad, and which actions are right or wrong. Notwithstanding the importance of continuing to reinforce the case for “why”, it can at times paralyse action. The ultimate goal is realising real world change – and therefore there is greater merit in acting towards a new way of thinking, rather than trying to think towards a new way of acting.

“Involvement = changing behaviour”

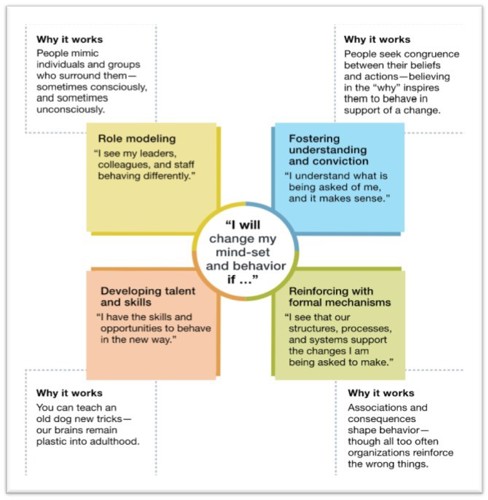

Increasing involvement, at its simplest level, requires women to change behaviour – whether increasing their existing sports activity, going back to their local club, choosing to volunteer at their children’s sports day or buying tickets to support their favourite athlete in the stadium. Framed in this way, we can think about this from the perspective of behavioural change. There is a deep well of research on the topic and one helpful framework identifies 4 key requirements for an individual to change their behaviour:

Source: McKinsey

The fundamental insight of the four-part framework is the following: if and only if all four conditions are satisfied do I change my behaviour – each condition is necessary but not sufficient.

I will get involved in sport if…

…I understand why I should get involved and it makes sense to me

In terms of fostering understanding and conviction there has been some success in “landing the message” on sports participation. In the UK 75% of women 14-40 years old say they want to be more active and over 90% of women of a recent study in America showed awareness that increased physical activity would decrease their risk of coronary heart disease . This suggests there is a genuine desire amongst women to be more involved in Sport and an understanding of its importance for maintaining health.

…I see women leaders, colleagues, and others involved in sport

In a similar way there has arguably been notable success in the promotion of women role models. In 2017, 1.1million people watched the Women’s Cricket world cup final in the UK (with 180 million global viewers across the whole tournament which is a 300% increase from previous World Cup in 2013) and 9.7million people watched the Rio Women’s hockey final on the BBC. 11 million people have also viewed the This Girl Can campaign which champions ordinary female participation and directly tackles the women’s’ fear of being judged in some way; whether not being skilled enough, fit enough, or the right size to participate in sport.

…I have the skills and opportunities to get involved and

This is an area where much more could be done. While public investment into women’s facilities and pathways to women’s participation has increased in many countries this is not matched by private sector investment. Only between 0.5 and 1 percent of sponsorship expenditure in the UK is spent on women’s sport, with an even smaller percentage being generated through broadcasting rights. This means less money to pay elite female athlete wages, less support for women’s sport teams at an amateur level and less commercial R&D into the women’s game. Change will require a fundamental shift in the economics of the sector, and/or more aggressive government intervention in the market.

…I see structures, process and systems to support me to get involved

Outside of participation, the success of attempts to offer more concrete pathways for careers in sport for women remain limited. Sport England has recently tried to make it easier for women to reach senior leadership positions by mandating that National Governing Bodies to have at least 30% women on their board. Whilst a positive step, appointment of non-executive director positions does not necessarily establish the mechanisms to support a rise to the top over the course of a full career.

Action on two fronts

There are two insights from this behavioural change approach that should immediately be acted on.

First, measures that address skills and systems are needed as much as, if not more than, redoubling of efforts on perception and role models. A more holistic programmatic approach that addresses all four areas simultaneously, or that boost co-ordination between targeted efforts would yield greater results.

Second, the framework places the individual at the centre of change. Understanding individual drivers of behaviour is more difficult and more expensive than generic research on the overall population. Campaigns such as This Girl Can clearly shows the impact of genuine insight-led intervention but was built on two years of extensive research. Big-data analytics and technology now enables us to draw insights into individual behaviour at a micro level much faster and more cost effectively. The retail sector has successfully harnessed this to fully exploit individual consumption preferences and behaviours to nudge us towards purchase. If retailers can use data to make us part with our cash, then surely, we could use data to get women more active and involved in sport, to benefit not just women, but society as a whole.

The approaches and technology are already available. It is now time to act on, not just think about, changes for women in sport.