The health benefits of physical activity are widely acknowledged, however almost 40% of people in the UK are inactive, with over half of inactive people saying they want to be more active. Why then, despite significant investment, have physical activity levels not materially increased in the last decade? There is clearly a disconnect between people wanting to be active and actually becoming active. We must bridge this intention-action gap.

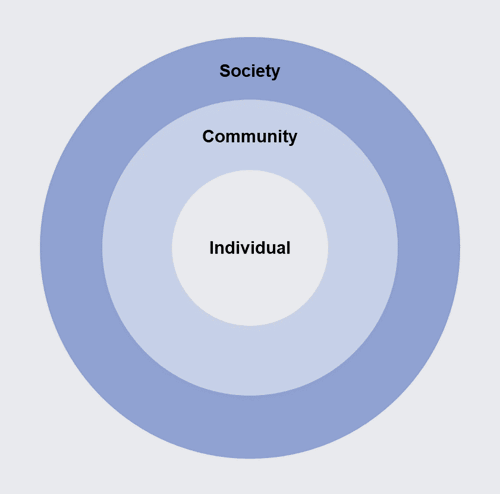

This article outlines how we can bridge this gap by adopting a comprehensive approach that simultaneously addresses physical activity behaviours at three levels: developing a society which promotes physical activity; running programs in communities that provide compelling opportunities to be physically active; and providing individuals with personalised support to develop sustainable active habits.

Figure 1: All three levels need to be addressed to bridge the intention-action gap

SOCIETY – SHAPING THE LANDSCAPE

Our society influences our physical activity through a combination of social and structural factors. Social factors can be things like cultural values and the presence of role models. Structural factors range from infrastructure, skills to rewards schemes.

Society can influence whether people cross the intention-action gap. A good example of this is swimming. 500,000 fewer people swim regularly now compared to 2010[3].

This is despite the fact that social factors seemed to support an increase in swimming participation over this period. After the 2012 Olympics in London, swimming was the second most popular Olympic sport that the public wanted to participate in and large numbers of people signed up to swimming programs[4].

Structural factors however were not supportive. There was a lack of workforce and not enough swimming pools to meet the demand, with long waiting lists at many pools. Furthermore, people were not provided with the skills needed to swim. A 2016 report identified that one in three children leave primary school without being able to swim[5]. Incentives were also not aligned. In 2010, the government ended a policy that provided free swimming to under 16s and over 60s despite there being a 50% increase in young swimmers since the scheme's introduction[6].

This example is one of many which underlines that society should be the first consideration in any policy to boost activity, and alongside our recent article on women in sport highlights the need to address both social and structural factors to achieve results.

COMMUNITY - HEADING EAST

Communities are a key part of society. Programs provide communities with opportunities to be physically active. Community programs today however often have little impact on physical activity. A 2014 report by Public Health England evaluated 952 programs and found no “proven practices” to improve physical activity[7].

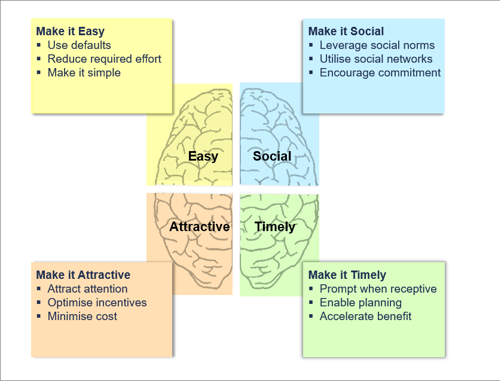

A possible solution to this lies in applying behavioural science to the design of community programs. The premise of behavioural science is that people can be influenced to make ‘better choices for themselves’ through well-structured interventions. This is summarised in the EAST framework below.

Figure 2: EAST framework

Parkrun is a volunteer-led weekly, timed 5km running event which anyone can participate in. Since it started in 2004, it has grown to having over 130,000 runners regularly participating[8]. The event comes straight from the behavioural science playbook:

- Easy: The 5km distance is achievable for most levels of fitness. The registration process makes it simple to take part for first time runners. It takes place in parks across the country, so people can join a run close to their home reducing required effort to participate.

- Attractive: It is visible in parks across the country – attracting attention of potential participants. It is free, minimising cost. It also provides clear incentives, for example participating can reduce your insurance premium.

- Social: Parkrun fosters a local running and volunteering social network. Its tagline “it’s a run, not a race” captures how it wants to be seen as a supportive and friendly rather than competitive event. This encourages friends to run together which encourages commitment.

- Timely: Events are held at the same time every week, so there is frequent opportunity to participate. This enables planning and means that it is easy for people to build into their routines and use it to set and track fitness goals. Recognition is given to participants who achieve personal bests or participate in a high number of runs. This accelerates the benefit to participants by giving them a sense of achievement immediately after each run.

The example of Parkrun shows that community programs can be effective when the design comprehensively covers all four components of the EAST framework – and does so not just for a single user type but for multiple target groups.

Individual - Making it stick

Despite Parkrun’s success, 30% of the 2.7 million people who have participated globally do not do more than 1 run and over 50% don’t do more than 3 runs[9]. This suggests we need to do even more to sustain behavioural change.

Quitting smoking can be argued to be analogous to getting active as most people want to quit but are not able to. Quitting rates in the UK have increased significantly in recent years from 13.4% in 2010 to 19.8% in 2017[10]. Initial analysis suggests this is due to a combination of changing the environment through effective legislation and intervention led change based on good behavioural science – e.g. providing more substitutes such as e-cigarettes makes quitting easier, high duty rates makes smoking less attractive, banning smoking in enclosed spaces makes it less social, and prominent health warnings on packaging provides a timely deterrent.

However, the UK Department of Health and Social Care highlights personalised individual support as the most important factor, citing that smokers who use local Stop Smoking Services are up to four times more likely to quit successfully. These services focus on habits – the unconscious decisions which account for 43% of what we do every day[11]. They provide support in understanding individual habits, tailor-made plans, support groups, equipment and coaching to replace old habits with new ones. It also recognises that changing habits can take over 8 months and therefore focuses on long-term sustainability.

Many physical activity interventions are short-term initiatives. This often results in short-term success that is not sustained. Imagine the impact if we supported people at an individual level to help them make new physical activity habits stick.

It’s time for a comprehensive change approach

We must make a concerted effort to bridge the intention-action gap. To do so, we must make changes effecting behaviours at a society, community and individual level. Furthermore, each level of change should not be considered in isolation. We need to implement this in a comprehensive approach that addresses all three levels simultaneously.

What could we achieve if we could do this successfully? Convincing just 1 in 5 inactive people in the UK to cross the gap would result in approximate 8% increase in physical activity in the UK. In London, getting an extra 1.7 million people active could lead to £2.75 billion of economic, health and social benefits[12].

The time for intention is over. The time to act is now.

[1] Active Lives Survey, Sport England

[2] Active People Survey, Sport England

[3] Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2015/jul/05/olympic-legacy-failure-sports-participation-figures

[4] YouGov https://yougov.co.uk/news/2016/08/03/athletics-swimming-and-track-cycling-are-brits-fav/

[5] ASA - http://swimming.org/~widgets/ASA_Research_Library/School%20Swimming/SS1%20-%20Save%20School%20Swimming,%20Save%20Lives%202012.pdf

[6] BBC - http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10343421

[7] Public Health England - https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/374560/Whatworksv1_2.pdf

[8] parkrun.org.uk

[9] wikiparkrun https://wiki.parkrun.com/index.php/Club_Membership_(5km)_Totals

[10] Smoking in Britain – Quit success rates in England 2007-2017

[11] Psychology of Habit – Wood and Runger

[12] Portas analysis – Active Citizens Worldwide