There is a significant drop-off in physical activity as individuals move from youth into adulthood. In England, for example, this drop-off is as much as 60% over this period [1]. To shift the needle on societal levels of physical activity, we need to change the way we form lasting physical activity habits in youth.

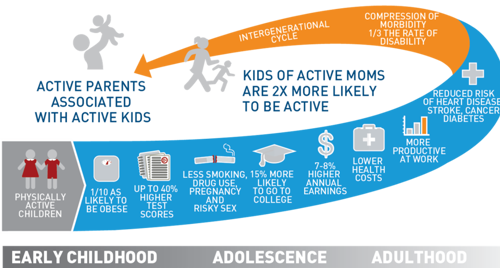

This article outlines the critical activities or ‘interventions’ that should be used at different stages of a young person’s development in order to develop sustained and lifelong activity habits. Getting this right will result in health, social and economic benefits that are compounded over lifetimes and across generations (see Figure 1) and may even result in extending lives by as much as five years[2].

Figure 1: The compounded benefits of lifelong physical activity (credit: Aspen Institute)

THE PATH TO LIFELONG PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

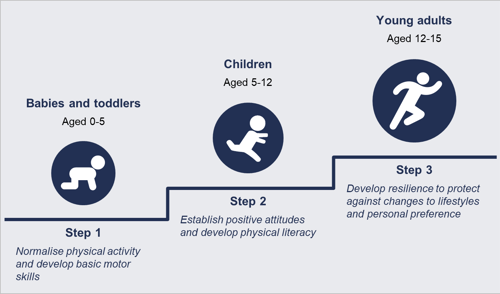

The first three phases of life are critical to habit development (Figure 2). By designing interventions specific to each stage of a child’s development, we can ensure that the youth of today set out on the path to lifelong physical activity.

Figure 2: The first three steps of a young person’s life and the critical actions required to establish lifelong activity

STEP 1: BABIES AND TODDLERS (AGED 0-5)

For babies and toddlers, being active should be established as a core part of normal everyday life. It is also important to leverage the opportunity to develop basic motor skills.

Early experiences are increasingly recognised as fundamental to habit formation. For instance, Sport Australia has recently announced the development of their first Early Childhood Activity Strategy to “improve the quality and amount of physical activity for children under five”. A recent academic study also demonstrated that physical activity habits are largely established by age 11–12 years, and influencing these patterns requires intervention before children are 5 years old[3].

To address this, we should:

- Target parents to make physical activity a part of their children’s everyday life – Young children are heavily influenced by their parents. Children with active mums are twice as likely to be active[2], while children with obese parents are three times more likely to be obese than children with healthy weight parents[4], and 70% of children who had at least one parent playing a sport also participated themselves[5].Not enough is done to leverage this parental influence. Programmes and facilities should be family friendly to facilitate parent-child participation. Campaigns directed at parents should convey the importance of physical activity to their babies and toddlers and tackle any misconceptions around this age group being too young for exercise. Campaigns should also be targeted at expectant and recent mothers to tackle the drop-off seen during and after pregnancy, with sporting mums – such as Serena Williams or Alysia Montaño – engaged to demonstrate what can be achieved.

- Design age-specific interventions to develop basic motor skills – Programmes should deliberately develop basic motor skills in young children. A good example of this is Playball, whose programmes target narrow age groups based on their specific cognitive, social and motor needs. The focus starts on building the basic foundations of movement and moves all the way up to teamwork and more complex ball skills, depending on the age group. This enables young children to develop and become competent in the basic movements needed for future physical activity.

STEP 2: CHILDREN (AGED 5-12)

For children, it is important to establish positive attitudes and develop physical literacy to set them up for success in future activities.

A positive attitude to sport and physical activity are the foundation of lifelong activity habits, with most children deciding whether they are interested in sport between the ages of 5 and 12. It is therefore critical to establish the intrinsic motivation and ability to take part during this period.

To address this, we should:

- Develop a positive attitude by focusing on fun, not competition – Enjoyment is the biggest driver of activity levels in children[6]. This should be the foundation of programme design. Netball New Zealand, for example, have implemented a policy that ensures junior players rotate position and play at least half a game. This gives everyone the opportunity to enjoy playing the game and has contributed to netball being the most popular sport for women in New Zealand[7]. This focus can also be embedded through national policy. In Norway, clubs are prohibited from publishing match results or race rankings until age 13. This focuses coaches and volunteers on the personal development of each child as opposed to the competitive element of sport, which can otherwise put off children.

- Establish the foundations of physical literacy – Physical literacy is “the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life”[8]. Achieving this is critical, as physically literate children do twice as much activity as other children[6]. One element of this requires equipping children with the competence and confidence to play sport. Many, however, are never provided with clear guidance on fundamental movement skills such as how to throw or catch a ball. The 60 Minute Kids’ Club is a programme that concentrates on establishing such skills. Through its online tools, it supports students to understand and develop these skills, and shares progress with teachers and parents. Thousands of students have taken part, with schools reporting participation rates up to five times higher than other programmes[9]

STEP 3: YOUNG ADULTS (AGED 12-15)

For young adults, developing resilient habits is vital to safeguard activity levels against changes to lifestyle and increasingly competing priorities.

By now, young adults have developed preferences and are more likely to participate if the activity suits their lifestyle. Young adults also have increasingly competing priorities, so it is important to reduce barriers that could undermine emerging habits. Measures should be put in place to develop resilience and so safeguard against future lifestyle changes.

To address this, we should:

- Provide choice and tailor programme design – It is important to provide young adults with a wide choice of sports, both inside and outside school, so that each individual can find the sport that is right for them. Sporting Schools, for example, is an Australian Government initiative which has already funded over 500 secondary schools. It aims to provide choice to students, with over 30 sports currently delivering programmes across the country. Programme design should also be tailored to meet young adults’ changing needs. For instance, when New Zealand Small Blacks split their rugby programmes by gender for U13s and above, they increased participation by 9%.

- Provide local opportunities to be active – Proximity of facilities is a critical factor for this age group. In the US, kids living within one mile of a park are four times more likely to use them than if they live further away[2]. One initiative that addresses this is Street Games, which manages a network of organisations to target disadvantaged youths by “bringing sport to their doorstep”. Programmes and events are made more affordable and accessible by bringing them directly to areas of high demand but low supply. This approach has been a great success, with over 100,000 youths taking part each year[10].

- Encourage participation in multiple sports – Specialising in one or two sports prematurely has been shown to be detrimental to lifelong habits, as young adults often do not develop the skills and desire to enjoy a variety of sports throughout their lives. According to Sport England, a “greater proportion of current regular participants focused on two or three main sports when aged 11-16 compared to less active or non-active people”[11]. Engaging in multiple sports is therefore important to develop resilience to ensure continued participation into adulthood.

STARTING ON THE RIGHT PATH

Together, these interventions form a set of guiding principles for governments and organisations hoping to establish lifelong physical activity in youth.

The benefits to individuals and society if we get this right are huge. Even a 10% increase in youth activity levels in England would equate to 300,000[1] more children who are healthier and happier. If we think back to Figure 1, these children would be ten times less likely to be obese and would likely have greater success in their future professional and personal lives[2]. This impact is compounded, meaning it doesn’t stop with these individuals but will also affect subsequent generations as well as society at large.

To realise these benefits – and not deprive future generations of a lifetime of enjoyment – we must help the youth of today take their first steps on their path to lifelong physical activity.

[1] Sport England Active Lives Children and Young People Survey 2018

[2] The Aspen Institute Project Play

[3] BMJ: Trends in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in adolescence

[4] Health Survey for England 2017: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2017

[5] Australian Sports Commission

[6]Sport England Active Lives Adult Survey, Active Lives Children and Young People Survey 2018

[7] Active New Zealand Survey 2017

[8] The International Physical Literacy Association, May 2014

[9] https://www.changemakers.com/playexchange/entries/60-minute-kids-club

[10] https://www.streetgames.org/

[11] Sport England report: How to develop a sporting habit for life (2012)