Physical inactivity directly contributes to one in six deaths in the UK and costs business and wider society over £7 billion a year, what then can we do to improve physical activity. [1]

Research shows that childhood physical activity levels are key predictors of physical activity levels in adulthood. The correlation of low activity levels in childhood to low levels in adulthood is particularly strong. Nearly 80 per cent of the 7 million children aged 5 to 15 in England are not doing regular exercise.[2] If we want to improve physical activity rates, we need to change the way we develop physical habits in children.

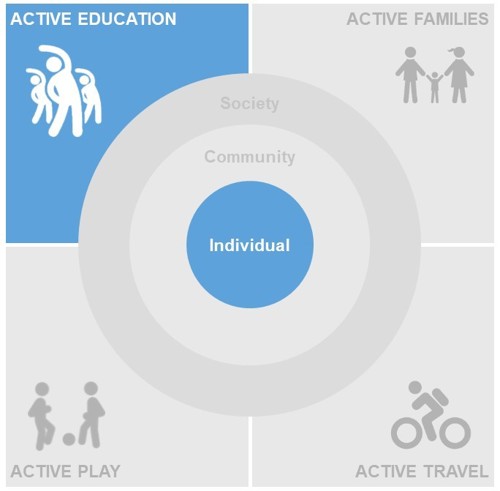

To do this, we need to adopt a 24-hour approach – focusing on supporting physical activity in all aspects of children’s lives: school, recreation and rest, family time and travel time. We also need to apply a comprehensive approach that simultaneously addresses physical behaviours at three levels – society, community and individual, as outlined in our article on bridging the intention gap.

This article focuses on active education and individual change. In particular, it outlines how we could promote life-long activity in youth by transforming Physical Education (PE) at school – placing habit formation at the centre. It is worthwhile to note that, whilst PE is not the only opportunity to influence habit formation in children, its importance is clear given its established place within our lives (see Diagram 1).

Diagram 1: PE is a key component of active education and a core part of making this work is focusing on individual habit formation

Understanding habits

Habit can be defined as automatic behaviour, or a choice that at one point was made deliberately but has transitioned to being made without thinking. Habits are a big part of what makes physical activity stick. Habits are what gets a runner out of bed on a winter morning when a thorough analysis might support hitting the snooze button. Their willpower occurs without them even thinking about it. Research shows we get spikes in brain stimulation when starting a habitual activity due to our expectation of the outcome from that activity. Our perception of effort levels also reduces when doing a habitual activity. Our neurology means habits are a rewarding option, and therefore one we are more likely to sustain.

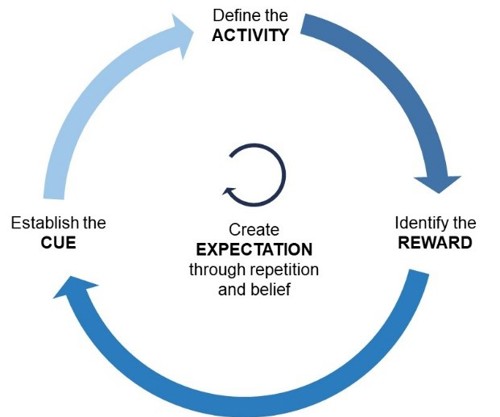

Habit formation can be established by applying a four-step framework: define the activity, identify the reward, establish the cue and create expectation through repetition and belief.

Diagram 2: Habit formation framework

Assessment of PE in England against the habit formation framework

PE plays a critical role in establishing physical activity habits. The content of the curriculum in England focuses on developing the skills required for physical activity, however analysing it against the above framework shows clear room for improvement in supporting habit formation:

1. Establish the cue

- Habits are triggered by cues, which are different for different people. Several studies have examined physical activity in youth however most have focused on the 14-25 age bracket, are based on small sample sizes, over short time periods and tend to highly generalise about people’s cues and motivations, and so are limited in their impact.

- On average, primary school teachers receive just six hours’ training in delivering PE lessons. This sells them short in delivering even the basics of PE, let alone complex behavioural coaching. To support habit formation, it is necessary to conduct deeper analysis on children’s motivations, and train PE teachers and coaches in this theory and how to apply it.[4]

- Research has shown that habit formation is strengthened by conscious action planning. It is therefore important students understand their own behavioural cues, however PE classes focus on maximising active time and rarely allow time for self-reflection. Imagine the impact of a PE curriculum where students regularly set personalised physical activity goals, make plans to achieve them and reflect on their progress.

2. Define the activity

- Sport England defines physical activity as doing at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity per week. Establishing a routine to achieve this each week is not reflected in the current PE curriculum.[3]

- Habits can be vulnerable to changes in environment. This is reflected in the drop-off in activity after leaving school. More needs to be done to encourage children to form routines that are robust to changes as they grow older. For example, some schools incentivise students to cycle or walk to school by providing breakfast vouchers.

3. Identify the reward

- It is important to design PE lessons to provide children with immediate reward. Research shows a key factor in improving children’s experience of PE is giving them a choice over which sport they participate in, thus giving them a sense of control. Other factors include positive teacher-student interaction, perceived competence and positive social interaction with peers.

- PE is still treated by many schools as optional. Research from the Youth Sport Trust has revealed that 38% of secondary schools have cut PE over the last five years due to exam pressures. This will influence how children perceive the value of physical activity. PE should be approached with the same approach as academic subjects, with regular feedback delivered in class and results valued equally to those in other subjects.[5]

4. Create expectations through repetition and belief

-

To reach the stage of sustained habit, a person must have regular opportunities to repeat the activity, cue and reward loop. It is unlikely that 2 hours of PE a week is sufficient to form a habit of 150 minutes of moderate activity a week. Furthermore, many primary schools do not comply to the 2-hour recommendation and those that do struggle to get two hours of activity out of a two-hour slot in the timetable.

-

Research shows that even well-formed habits can be fragile when placed under stress, and that habits are more resistant to this when accompanied by positive belief.

-

Alcoholics Anonymous, a program millions credit with saving their lives, has credited its success to surrounding participants with a community who help them believe change is possible. How many young people stop being physically active because they don’t believe they are sporty? Instead of fostering this kind of feeling, we should use PE to create an environment where children are encouraged to inspire and support each other to achieve their goals.

Habit formation is also undermined by a lack of robust measurement of children’s physical activity, fitness and physical literacy. Sport England is launching an Active Lives Children and Young People survey in 2019. This will be a good first step to combat this, however a consistent measurement approach needs to be established with input from the Department for Education, Ofsted and schools to generate the evidence base required to improve children’s activity rates.

England is not alone in its need to improve PE. The proportion of children in the UK (23% boys, 20% girls)[7] meeting WHO guidelines of 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity per day is broadly comparable to other countries such as Australia (fewer than 20%), Canada (9%) and Sweden (21% girls, 13% boys).[8] The time allocated to PE is also in line with international status quo – with the global average being 103 minutes weekly in primary school and 100 minutes weekly in secondary school[9], although it is less than France which imposes the most PE time of any EU country (primary 220 minutes a week, secondary 165 minutes a week). England was also assessed as having comparatively good delivery of PE relative to other countries in the Active Healthy Kids Global Alliance Scorecard.

It’s time for a new habit

We urgently need to transform our approach to establishing physical activity habits in children by overhauling the PE curriculum, placing habit formation at the centre.

Furthermore, we also need to look at the other opportunities to influence habit formation as suggested in Diagram 1. Families, for example, are uniquely placed to understand and support children’s habits. Sport England’s Families Fund launched in July 2017 will provide up to £40 million to projects that support families with children to get active together.[10] This is a great development however further funding, policies and initiatives will be needed to drive a substantive change.

We are at risk of depriving a generation of physical activity, at a time when their physical and mental wellbeing is increasingly at risk. It’s time for us all to form a new habit – a habit of promoting lifelong activity in youth.

[1] Public Health England - https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health/physical-activity-applying-all-our-health

[2] Public Health England - https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/374914/Framework_13.pdf

[3] Sport England - https://www.sportengland.org/research/active-lives-survey/

[4] Guardian - https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/22/exercise-schools-pe-lessons-exams

[5] Youth Sport Trust - https://www.youthsporttrust.org/news/research-finds-whistle-being-blown-secondary-pe

[6] Department of Education - https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-physical-education-programmes-of-study

[7] NHS - https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publication/0/0/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2018-rep.pdf

[8] Active Healthy Kids - https://www.activehealthykids.org/the-global-matrix-2-0-on-physical-activity-for-children-and-youth/

[9] UNESCO - http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002293/229335e.pdf

[10] Sport England Families Fund - https://www.sportengland.org/media/11822/sport-england-2016-17-annual-report-and-accounts.pdf